Crafts and Religion

he Museum of Ceramics of Castelli (Teramo), housed in the convent of St. Mary of Constantinople, holds hundreds of majolica artifacts, a typical production of the small town in Abruzzo, in which between the 16th and 19th centuries several families of ceramists (Cappelletti, Fuina, Gentili, Grue, Pompei) distinguished themselves for their mastery.

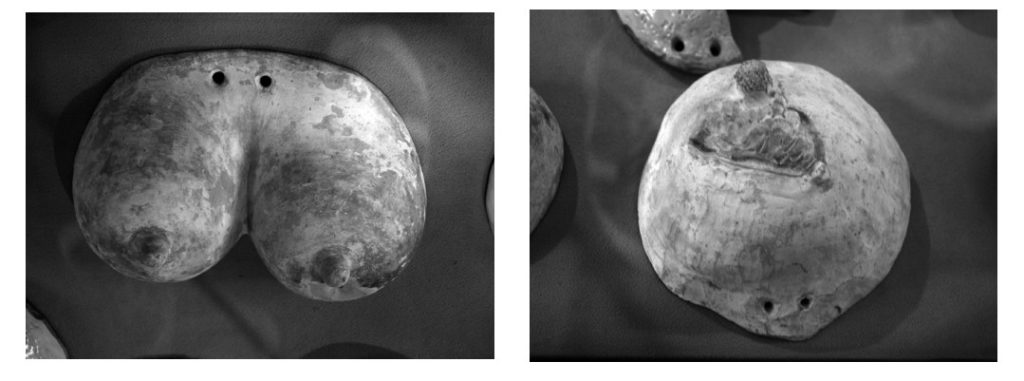

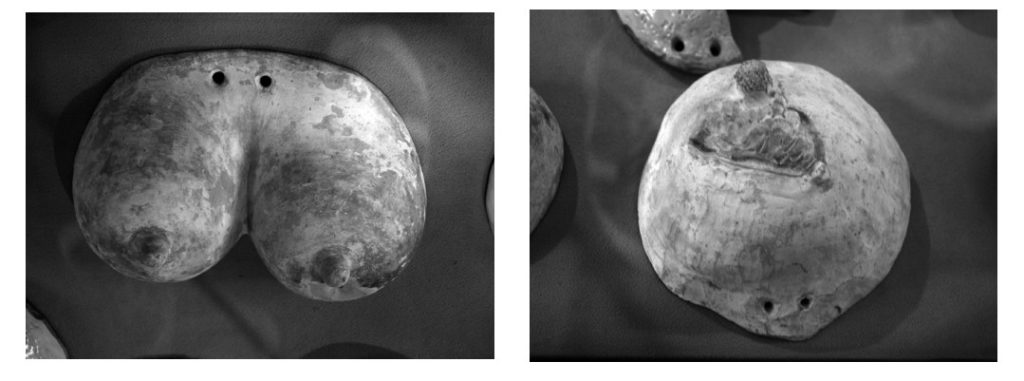

These ceramic artifacts are presented in a unique category of objects (anatomical votives in the form of breasts); votive objects, dedicated to St. Roch, in the form of breasts that from the medical perspective, depicts medical pathologies that afflicted a good portion of the female population in Antiquity in those places.

Preliminary to any art-historical analysis is a reflection on the saint after whom the church from which the anatomical votives came is named: Roch of Montpellier is a Catholic saint who is highly venerated as a protector against the plague and infectious diseases in general (recent liturgical updates also recognize his patronage against AIDS), but despite his popularity, little or nothing is known about his life. Born almost certainly in the French city of Montpellier between 1345 and 1350, he is assumed to have died in his early thirties (between 1376 and 1379) in Voghera ( Italy ) . From this center his mortal remains, more than a century later (1485), were moved (stolen, according to tradition; legally acquired, according to more recent studies), and placed in the church dedicated to him in Venice, the city of which he became co-patron. In classical iconography, the saint is depicted in pilgrim garb while pointing with his finger to the plague sore on his thigh and with a series of features and symbols that are repeated more or less constantly: a wide-brimmed hat, a tabard with related cape, a staff, a saddlebag slung over his shoulder, a water-bottle gourd (often hanging from the staff) and shells for drawing water (a symbol par excellence of pilgrims), fixed on the cape or on The cult of St. Rocco in Castelli and the anatomical votives in majolica hat. Completing the depiction are a dog with a piece of bread in its mouth, at the saint’s feet, and (more rarely) an angel carrying a tablet indicating anti-pestilence patronage (“Whoever invokes my servant will be healed”); in some cases there are also a pair of attributes identifying him as a medical student (Montpellier was at the time one of the most important universities in this field): a small flask attached to his girdle (which could indicate a medicine container) and in his hand a small lancet scalpel, which just then was beginning to be used to incise boils and thus encourage the escape of pus. An additional element of St. Roch’s iconography that may have played an important role for the Castelli community is a red cross on his clothing, on the side of his heart, to indicate the cruciform angioma that the saint had on his chest from birth, and which was the feature that allowed him to be recognized by his grandmother and maternal uncle Bartholomew when he was prepared for burial after his death in prison in Voghera ( North Italy ).

Some sample of ex-voto

Figure 1

Figure 2

How can we explain these breast-shaped votive offerings?

In past centuries people depicted in the form of objects the will to ward off illness or misfortune by offering them to a saint or Deity. These artifacts depicting female anatomical parts in ceramics are no exception.

Throughout history, woman has constantly appealed to the deities who presided over breastfeeding and protected mother and child so that minor inconveniences and major problems could be solved. Historically, woman has walked a difficult path, full of obstacles and illnesses; her greatest concern was that she would not be able to continue breastfeeding, thus precluding her baby from the only known source of food: breast milk.

From the year 1330, the spread of wet-nursing among the upper classes made the living conditions of children increasingly precarious and dramatic, leading to a significant increase in infant mortality due to increased malnutrition and infant intestinal disease. In 1762, the Swiss philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote in his Emile, “I harshly blame the women who entrusted their children to wet nurses, depriving them of their mother’s milk.” The climate of those years agreed with the type of mentality, and there was a return to breastfeeding, resulting in a reduction in infant mortality. The dating of the castellan votive offerings coincides perfectly with the climate of the time; the considerable demand for breast protection and healing explains the prevalence of such “sympathetic” votives among those found in the rural church of St. Roch. The high incidence of lesions compatible with mastitis and congestion of the galactophore ducts evident in the votive offerings would confirm the importance devoted to breastfeeding and its noble significance in the female population of Castelli. The significant number of depictions compatible with neoplastic lesions would indicate a high incidence of breast cancer pathologies, leading to the suspicion of a particular genetic predisposition in the Castellan population to the development of familial breast carcinomas, worthy of further in-depth scientific study.

All Saints plus One

One of our Apulia travel packages to discover how the Deities of the 1300s are our recent Superheroes

Mail Us – Taylor made Trips

Address

via Ammiraglio Millo, 9 ( Puglia – Italy )

info@ailovetourism.com

Phone

+39 339 5856822