OLDEST ARCHAEOLOGICAL REMAINS OF “BREAD” AND RELATED PRODUCTS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND EUROPE

A universal food par excellence, bread, in its many forms (loaves, buns, flatbreads, etc.), has been throughout human history one of the main sources of subsistence for ancient peoples. A seemingly simple food, it has been and still is an expression of complex cultural, social and symbolic universes, probably more so than any other nourishment

In truth, bread constitutes one of the most elaborate and refined cereal products, being the result of a series of operations involving the use of specific technologies to make it, such as the production of flours, more or less long times to ensure its rising, as well as the construction of ovens suitable for its baking. Bread also constituted a very useful food reserve in times of famine: it could be dried, preserved and reused.

Beyond the numerous historical and ethnographic sources available for the Mediterranean and Europe, archaeological finds of breads (and related products), recovered as early as the late 19th century, that is, at the dawn of modern archaeology, are rather rare. Among the earliest finds, the best known is surely that of charred loaves collected by Keller in prehistoric villages around Swiss lakes3 ; and it was followed by the far more numerous ones of cremation burials from Birka, on the island of Björkö (Sweden), from medieval times4 . Although they had greater resonance, the famous Egyptian loaves preserved by drying in ancient Egyptian burials were not discovered until later: occasional references in excavation reports of the time, such as Petrie’s in connection with the Qurneh excavation5 . As far as the chronological attribution of the finds is concerned, and contrary to what was assumed, leavened doughs from European sites are very old, with the earliest records dating back to the fourth millennium BC, such as the remains from the Twann site (Lake Biel, Switzerland) dated to ca. 3,900-3,500 BC, and those from the Montmirail site, dated to 3,719-3,699 BC.

CONSERVATION MODES AND ANALYTICAL APPROACHES

From an archaeological point of view, bread, as an organic compound, can be preserved in archaeological deposits only under special conditions, and this has certainly made it among the least common archaeological remains, and therefore of exceptional value.

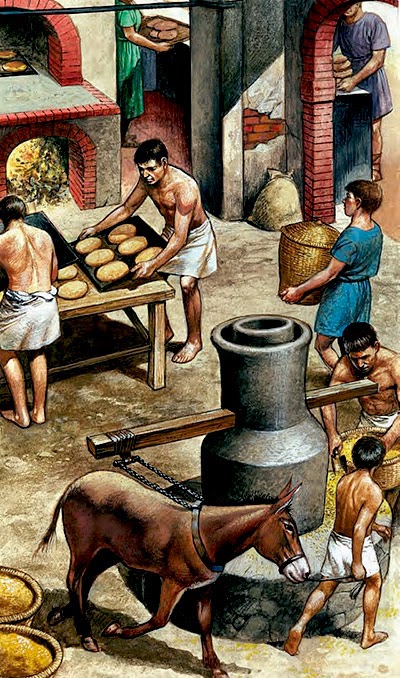

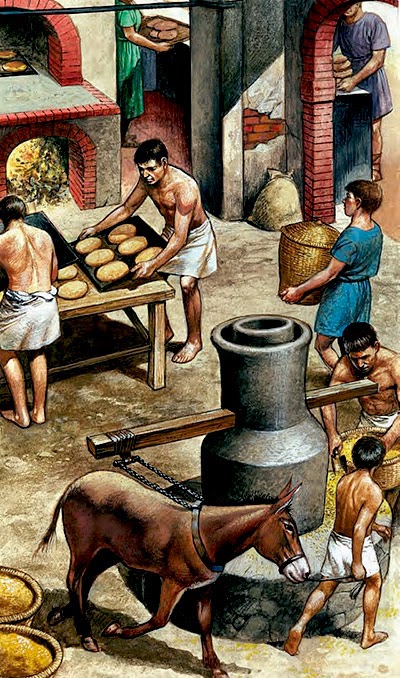

It is usually preserved because it is charred (thus devoid of those elements that attract decomposers); combustion can be accidental, for example during an error in the cooking process, or voluntary, related to ritual or religious practices. Catastrophic events can also contribute to the preservation of such remains; this is the case, for example, with the breads found in the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FINDING CONTEXTS

The archaeological context of origin plays an important role in the interpretation of bread remains, especially when research is also geared toward reconstructing the socio-cultural, as well as economic, value that this foodstuff held in ancient societies.

In fact, bread produced for more or less daily food needs was intended for humans and, therefore, consumed; only accidental events could have allowed its preservation (this is the case, for example, with the remains of Pompeii and Herculaneum).

On the contrary, the finds of breads and related products turn out to be much more frequent in ritual, funerary and cultic contexts; although they are not everyday products (because they are linked to specific events in social life) their preservation from the archaeological point of view is ensured by peculiar “taphonomic”( ed. Phaonomy: science that studies the ways in which a fossil is formed) processes to which they are subjected. Offered to the deceased or to the deity, breads, buns, etc., are often connected to ritual forms involving the use of fire (incineration practices, offerings through combustion); their deposition takes place in protected places such as tombs and burials, or in special cultic spaces (votive pits, escharas).

THE MOST ANCIENT FINDS IN SALENTO

The conical bread of Roca. Currently the oldest attestation of bread remains for the Salento area, and more generally for Apulia, dates back to the 2nd millennium B.C. and comes from the Recent Bronze (12th cent. B.C.) levels of the site of Roca (Melendugno-Le), a fortified settlement that arose along the Adriatic coast of Salento during the Middle Bronze Age.

The site is characterized by different phases of life and, in addition to the aspects of monumentality that make it almost unique, particularly important are the cultural/ceremonial contexts related to rich and varied evidence of contacts with the eastern Mediterranean during the Bronze Age. It is precisely these aspects that, by underscoring the centrality of Roca’s political role in administering relations with the Aegean world, point to phenomena of cultural hybridization, including religious ones, with elements proper to the Minoan-Mycenaean environment.

That is, it would be an elaborate product, obtained by processing grains, ground until they were reduced to flour and mixed with a liquid, and which probably underwent fermentation processes; a kind of “bread” whose shape appears to be very singular. The “conical” shape of the dough refers mainly to Egypt where, over a wide span of time included between the 3rd and 1st millennium BCE, they are documented by molds within which they were shaped, called bread moulds, by terracotta reproductions25, by the hieroglyphic sign (bread-cone, conical loaf), which is attributed the meaning of “giving, presenting “, as well as by numerous testimonies in the figurative arts, including in scenes of offerings and sacrifices. Thus, it cannot be ruled out that the very shape of the ancient bread of Roca is not accidental, thus confirming the cultic value of the archaeological context of discovery.

The scones and taralli of Monte Papalucio. The main and most copious archaeological evidence of bread-related products in the Salento area consists of the burnt remains from the site of Monte Papalucio (Oria-BR), a sanctuary area located on a small relief of the present-day town and dedicated to the worship of the Greek deities Demeter and Kore. The place of worship, which has been archaeologically investigated since the late 1970s, is developed on a system of terraces placed at the foot of a cave. The construction of the sanctuary dates back to the Archaic period (6th-5th centuries B.C.) and coincides with a period of profound settlement transformation in Messapia; attendance, after a period of interruption, resumed in the Hellenistic phase (4th-3rd centuries B.C.), when there was a growth of the place of worship through a series of renovation works of the cult complex and the construction of new rooms.

The presence of mortars and lithic grindstones and the discovery of fragments of large food containers suggest that meals were prepared and consumed in the shrine and that some of the plant gifts were stored within the place of worship. In the votive deposits, in fact, the remains of fruits and seeds are abundant (various species of wheat and barley, various legumes including field beans, vines, dates, figs, pomegranates, etc.), but what makes the archaeobotanical assemblage unique in the ancient Mediterranean is the incredible wealth of charred remains of scones of various shapes.

The most interesting aspect of these finds, as already pointed out by Ciaraldi, is their almost perfect overlap, at least in form, with the sweets depicted in the votive terracottas of the likna found in the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore in Corinth (6th-2nd cent. BCE).

Excluded from this immediate comparison with the depictions in the likna are some of the remains from Oria, which instead find a fascinating as well as incredible parallel with one of the most typical baked goods of Apulian tradition, the so-called “tarallini” . These are precisely cakes with a peculiar ring shape, with a maximum diameter of about 2 cm and which, according to Ciaraldi, could be the stylized representation of the snake, an animal associated with thermophoretic rites.

“tarallini” from Oria ( Puglia – Italy)

The “tarallini” of Oria offer an interesting example of a long food tradition that has its roots in very ancient times. Over a long period of time this product, in some ways assimilable to bread (with which it shares the basic ingredients), has been filled with different social and cultural meanings than in the original context of sacredness (where it was also linked to food and meals, albeit with ritual significance), representing today one of the main symbols of conviviality, hospitality and friendly sharing.

All Saints plus One

Uno dei nostri pacchetti di viaggio in Puglia per scoprire come le Divinità del 1300 siano i nostri recenti Supereroi

Contact Us

Address

via Ammiraglio Millo, 9

info@ailovetourism.com

Phone

+39 339 5856822