Humans as a source of magical harm

We have already talked about how the supernatural, which we can include in a much larger group of phenomena that were called unexplained occurrences, was included and made a cogent and physically present factor in the Locorotondo area. Article here.

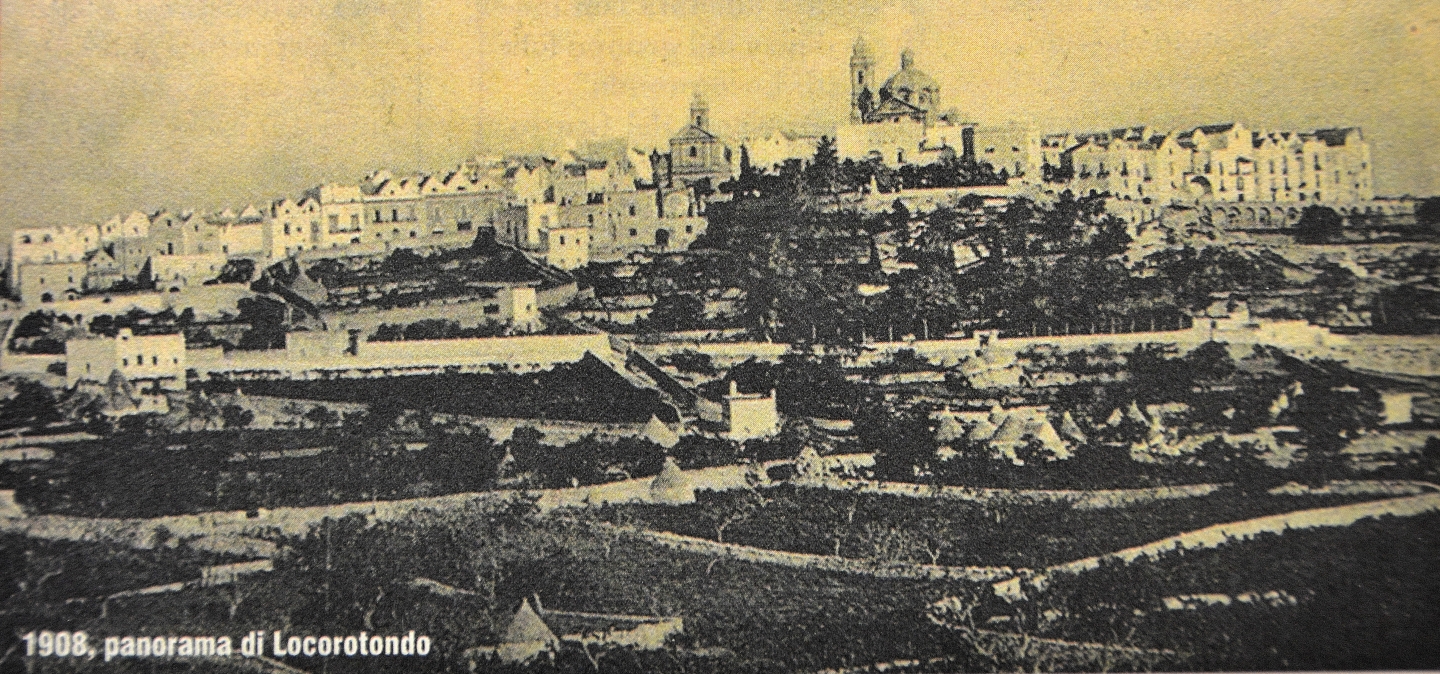

Locorotondo is, in fact, an example of a small town in the Murge region of southeastern Apulia that lives and lives with these traditions that reach superstitious heights. Compared to its neighboring towns such as Alberobello, Noci, Martina Franca was the subject of a real scientific paper in the 1980s, therefore, this information from which I draw the article is worthy of being dissected even after 40 years.

The belief in the evil eye is currently widespread and must be described in the Present tense. Obviously, a Present contaminated by the modern, rational structure of our society; therefore, the two terms afffascene (fascination) and ‘mmvidie (envy) have become mixed, becoming almost synonyms.

Affascene (fashion) e ‘mmvidie (envy).

Of the two forms of the evil eye, afffascene is the lesser. Signaled by the headache, it can be eliminated with the use of an oil-and-water oracle and cured with a spell. Anyone who learns them can use the phrases and oracle, but no more than three people in a lifetime are allowed to teach them, or they will lose the ability to cure. Amulets are ineffective against this form of the evil eye. Fascene originates from unexpressed envy or admiration of others, and there are some individuals-those whose eyebrows join their noses and are said to have eyes of affascene-whose envy is more likely to strike in this form. The target is usually a person rather than an animal or object, and what is envied in a person is often a quality associated with health, such as beauty or robustness. Also, not all people are equally susceptible to fascene, since the tendency to be afflicted with it is a hereditary trait that is concentrated in the blood.

‘mmvidie, or envy, on the other hand, can be severe, and its symptoms tend to manifest at times of bad luck or lack of health. Unlike affascene, ‘mmvidie cannot be removed; it just has to run its course. But, again unlike affascene, ‘mmvidia can be averted by various forms of amulet, to be worn on the person or attached to animals or objects that need to be protected. If ‘mmvidie can enter buildings through openings, particularly the threshold and chimney, these are often protected with an amulet-a horseshoe, a pair of open scissors-hung nearby. Parents protect children with an apetidde, a small cloth bag that is pinned to the inside of clothes and secretly filled with effective objects by a local witch (one should not look inside). When one fears the potential envy of others, such as, for example, when doing work, making the horns gesture with both hands prevents an attack. Similarly, a person who openly admires another can make this gesture and utter the phrase “D’a guardie” (“God protect”) – or, in the case of a possible victim of animai, “bènediche” (“blessing”) – to prevent envy from attacking. The source of ‘mmvidie is the envy of others, but in this case it is a type of envy that could be expressed openly through gossip behind the victim’s back and could be about fortune or new possessions. There are no individuals whose envy is considered particularly dangerous, and in several cases it was the envy of not one but several individuals that was considered harmful by the victim. Affascene and ‘mmvidie are, therefore, related but mutually exclusive concepts.

Magic and Intended or Unintended Damage

In neither form of the evil eye does the envious person knowingly inflict harm. However, according to tradition there are two ways of knowingly harming others: one, the curse, was right; the other, the adverse Fate, may or may not be. The elderly peasants of Locorotondo used to say, “I jasteime arrivene” (“Curses come,” meaning they hit the mark), expressing their belief that if someone who had been wronged consciously pronounced a curse against the offender, whatever was pronounced would come true. Another way of referring to the curse, a sentènse (judgment, as in a judicial sentence), emphasized the sense of justice implicit in the concept of a curse. A curse placed on an innocent person for wronging the cursor could come back to affect the latter. Curses often involved sudden affliction or the image of being hit by a bullet, as in “May an arrow [an attack of fear] strike you!” (“Cu te pigghie na saièttel”). Wishes for just harm were sometimes coupled with the name of God or Christ, as in “Vulève da Criste ca quante me n’a fatte passé a meé na passé jidde!” (“I want Christ to make happen to so-and-so what he did to me!”). Others were more colorful and figurative, such as “May the fate of a mouse happen to you in a cat’s mouth!” The victim of a curse had to live with this harm and, apart from avoiding the behavior that had wronged others, could do nothing to prevent or cure it.

The curses of marginally placed people hit the hardest. These were mainly women who had been abandoned by their boyfriends without provocation; unengaged women who had been deflowered or left pregnant and thus risked spinsterhood and disgrace; and parents, especially widowed mothers, who had been abandoned by their children. People greatly feared a mother’s curse. Particularly hateful cases of abandonment could lead to divine punishment on earth, and, as mentioned in the last paragraph, curses often invoked divinity. According to my informants, a man who dishonored his fiancée, abandoned her for another woman and then suffered misfortune or illness would elicit the phrase “I jasteime da’a zeite vècchie so chire” (“This is the result of the curses of his former fiancée”).

Individual atheists sought to magically harm others by going directly to a local witch to seek a spell. The victim of the spell suffered consequences ranging from inability to act to illness and even death. Atheist witches sold love magic to clients, which was considered a form of harm because it involved weakening the victim’s control of emotions (it was usually directed from women to men) and could ruin parents’ marriage plans for their children. Witches (mascère), or rather people who so identified themselves, existed and were identified by the community as such. My informants said that these were individuals who had formed a league with Satan and in return received a magical book, u livère de cummande (the book of “command”), and the knowledge to use its magic. People said that at any given time there were normally seven witches in the area and that they worked their most powerful spells and counterspells together. Witches were symbolically associated with sows: in one tale a flying witch is seen riding one, while in another she transforms into a pig and severely frightens her daughter’s fiancé by making him go rapidly back and forth on his porcine shoulders over the open mouth of a deep cistern. The children of the witch grandmother of one of my informants had seen her passed through a ritual fire by devils. “Innocent souls can see these things,” they said. The storytellers gave names to most of the deceased witches I heard about, and connected them to living people through kinship ties of no more than two generations. There were also some famous sorcerers, notably one named Michael d’Erchio, but their activities were attributed to a more vague and distant past.

Witches and Wizards

Witches also cured people magically, sometimes turning an illness into an animai, and provided powders and amulets believed to be effective against the ‘mmvidies and spells of other witches. Since they could both harm and heal, they were viewed ambivalently and were suspected of conspiring to prolong the treatment of each other’s victims.22 They were also suspected of conspiring to prolong the treatment of each other’s victims. In a story told by an old man about his childhood neighbors, some mischievous boys tripped a witch by stretching a thread across a path the latter often traveled. As they ran away, the witch shouted, “He who set the thread will have to come to me!” One of the boys began foaming at the mouth after arriving home, and his mother rushed to the witch’s house to ask him what to do. He replied that the boy himself had to come for treatment, otherwise he would die. The boy then went to the witch and threw himself on the ground, begging for forgiveness. My informant was sure that if he did not do so he would die because of the binding (hairs) that the witch had put on him.

Witches’ activities were believed to be mercenary, although in one case a witch provided her friend, a relative of the victim, with a free diagnosis of mortuary magic perpetrated by another witch. Malicious magic, like healing magic, was for a fee and was unavailable to those who used it out of malice or a desire for revenge. Unlike curses, magic could be used against the innocent, and there was no presumption that justice would be done, although those who felt wronged could turn to the local mascère in addition to uttering curses.

This is the case with the story of a young man who had emigrated to New York in the second decade of this century, abandoning his fiancée. When he later took up with a woman in the United States and decided to marry her, the spurned fiancée turned to a local witch, who concocted a letter that arrived in New York just in time to be delivered to the emigrant on the occasion of his marriage. The emigrant fell ill and his new wife sent the letter back to Locorotondo with pleas for help. The letter was shown to a locai witch, who immediately diagnosed it as an incurable mascigghia a murte, like a death spell, and shortly afterward the victim died. In another local story, an unrequited and vengeful suitor bought a speli that caused the object of his desire to have crises not only during the marriage, but also every time her new husband approached her sexually. An expensive treatment with another mascère was necessary to bring her back to normal.

Love magic purchased by a mascere was intended to capture the affection of an unwilling subject and was usually initiated by a young woman or her mother. This magic could be used to marry a young man with whom the woman was infatuated, or to ensnare a young man with high expectations of marriage and inheritance. Men explained that their mothers had warned them not to eat or drink anything in the home of unmarried girls in whom they had no serious interest.

Impersonal sources of harm

There were also several types of magical harm that resulted from impersonal sources that corresponded to neither a supernatural being nor a human being. The first of these is u tips a time in life when one is destined to be in danger. People learned about these points from the masceras or from itinerant specialists who attended markets and saints’ festivals in the area. There were “water points,” “fire points,” and “land points,” loosely associated with various types of accidents such as drowning, fire, or falling. The point predictors warned that they should be passed at certain ages, and people modified their behavior accordingly, especially if the predicted point had a more specific association. Those who had narrowly avoided an accidental injury-such as an elderly man who, as a young man, had tripped over a wall while hunting and whose rifle had gone off, burning, but missing, his face-spoke of having “passed a point.” There was not much one could do about points, except to be careful if they were expected, and all my informants professed not to know how they were formed or how they were intended for particular individuals at particular times in their lives. Having a point is morally neutral: there is nothing particular one can do to deserve it.

Another source of impersonal harm was temptation, literally “temptation.” Questions about the association of this concept with demons brought negative answers, although it was sometimes called d’u diavule temptation. Temptation occurred when a person deviated from a planned sequence of activities, often due to an unexplained whim, and thus became the victim of an accident. A city woman (who grew up in the country in a farming family) gave the following example. She had purchased a gas stove at an appliance store and the delivery man had brought the wrong model. She asked him to put it in a corner, but when he left, she decided to move it by advancing it a little at a time to a precarious corner. The floor was wet and the range slipped, falling on her and severely cutting her. The woman attributed the accident to temptation because she had moved the device on a sudden whim. The concept of temptation corresponded somewhat to the classic concern of the Azande, who, according to Evans-Pritchard (1937-69), needed to explain not only why a certain misfortune had happened, but also why it happened at a particular time when various circumstances coincided. Temptation drew people into harmful circumstances. If there was a stigma attached to the victim, it was the very personal one of having stupidly deviated from a straight and rational path.

Other impersonal sources of magical harm were omens and broken taboos. Most omens (malaiurie) portended harm, even if they could not be thought to cause it. Bad omens included crossing a priest’s path early in the morning, hearing a dog howling like a wolf at night, seeing a raven hovering over a house during the day, and seeing a black cat. The evil presaged by crossing the path of a priest could be averted by making the sign of the horns. Hearing a dog howling like a wolf was believed to be an omen of death, and several informants told of their experience.

Included in the same category, however, were several taboos that would bring harm if broken. The most commonly heard was that of burning a yoke: when an individual died a slow and painful death or remained in a coma for a long time before dying, people assumed that at some point the sick person had burned a yoke. To hasten the end, survivors would find a piece of yoke and place it under the dying person’s pillow. A couple I interviewed explained that the yoke was blessed because the cows and oxen were blessed and therefore burning it was a sin. They added that in the barn where Christ was born, the cow had kept the baby warm and was therefore blessed, while the donkey had blown the wind through and was therefore damned.

People observed several other taboos, but without the same awareness of their consequences. Olive oil and olive trees were considered blessed because during the flight to Egypt, after failing to find refuge in a field of broad beans, the holy family hid in an olive tree that the infant Jesus had commanded to be opened for them-that is why olive tree trunks are split and broad bean plants have thorns. On Palm Sunday, people continue to bring bundles of olive branches to church to be blessed and then place them in fields, on buildings and in rooms to obtain divine protection. Although some informants referred to the violation of a taboo as a sin, they mentioned it only as a careless action and did not suggest that it carries a special stigma for the person affected by its consequences.